NATIONAL HISTORY MUSEUM - HANOI

The galleries of the National History Museum in Hanoi (Bảo Tàng Lịch Sử Quốc gia) are housed in a colonial-era building constructed by the French School of the Far East (École française d'Extrême-Orient). Its collection is focussed on the early cultures of the northern provinces and the history of the Vietnamese dynasties from the Lý to the Nguyễn. (It also has some representative samples of Cham sculpture and Sa Huynh artifacts from the central coast.)

The original building was redesigned by the noted architect Ernest Hébrard, opening in 1932 as the Louis Finot Museum, named in honor of the founder of the Far East School.

The Đông Sơn period (Bronze Age) is well-represented by castings from of drums, bells, daggers, and figures that have been unearthed along the Hồng (Red) River and the Mã (Horse) River. The name Đông Sơn, meaning “East Mountain,” refers to the place where some of the first artifacts were discovered. The name “Đông Sơn” is commonly used for this style of bronze drum, which is found in southern China and in other parts of Southeast Asia. (Chinese and Vietnamese scholars have engaged in a long running and rather ahistorical dispute over which country can claim to be the original source of such drums.)

Bronze bell; figures shown coupling on the head of a bronze drum;

the famous “lampidaire” (oil lamp) excavated by the Swedish

Bronze bell; figures shown coupling on the head of a bronze drum;

the famous “lampidaire” (oil lamp) excavated by the Swedish

archeologist Olav Janse at the Lạch Trường site.

The local rulers of the Hồng River region were supplanted by a succession of Chinese invaders, the best remembered being Zhao To. Zhao To was a commander who had been sent to the southern region by the Qin court but became a semi-autonomous ruler after the short-lived dynasty collapsed in 207 BCE. Zhao To named his kingdom Nam-Việt—foreshadowing the modern name of Vietnam. Eventually the Han emperors were able to absorb Nam Việt into their empire, thus beginning the "Thousand years of Chinese Domination.” Despite its long duration, this period is represented by only a handful of artifacts.

Vietnamese leaders took advantage of the declining fortunes of the T’ang Dynasty to throw off Chinese rule in 938 CE. The first 70 years were marked by turmoil and dissension, including a struggle between the "Twelve Lords" of the Hồng River region. Finally, a young leader who had been raised in the Buddhist community managed to prevail in the power struggle. He proclaimed the Lý Dynasty in 1010, and this became the first stable imperial family in Vietnamese history.

Over recent years, the National History Museum has put more and more of the artifacts of the Lý on display, perhaps benefiting from the recent excavations of the western palaces of the royal citadel. Some of the carvings give us tantalizing glimpses of indigenous iconography, as well as influences from Indic as well as Sinic cultures.

The Lý Dynasty morphed into the Trần Dynasty in 1225, through the intrigue of one of the leading mandarins at the court, who engineered the marriage of his son into the royal family. Art from this period is often classified indeterminately as "Lý-Trần style."

Though it could use much more explanatory signage, the Lý-Trần collection is the highlight of the museum. There are some interesting vestiges of the brief reing of Hồ Quý Ly, but the Lê Dynasty gallery is underwhelming, while the accomplishments of the Mạc dynasty and the Trịnh and the Nguyễn lords are not represented at all. As a consequence, the Museum is limited to the story of the old “Đại Việt” of the north, with no accounting for the “nam tiền” (Southern Advance), i.e., the conquest of the Cham kingdoms along the central coast and the 17th century occupation of the Khmer territory of the Mekong Delta.

Upcoming: Vietnam Military History Museum (Bảo tàng Lịch sử Quân sự Việt Nam); Fine Arts Museum of Vietnam (Bảo tàng Mỹ thuật Việt Nam)

MUSEUM OF ETHNOGRAPHY

![]()

The Museum of Ethnography (Bảo tàng Dân tộc học Việt Nam) is well worth the trip to the outskirts of Hanoi city. (Speaking here of “old” Hanoi, not the contemporary Hanoi that has absorbed most of the adjacent rural provinces.)

The museum opened in 1997. The lead architect, Hà Đức Lịnh, is said to be of the Tày minority. The interior was designed by a French architect Véronique Dollfus.

For the western traveler, this probably the most entertaining museum in Vietnam, with marvelous displays of the country's dizzying array of ethnic cultures: Ede, Jorai, Bahnar, Cham, Bani, Tay, White Thai, Black Thai, Hoa (Chinese), Khmer, Kinh (Viets), and so forth. Video displays show village craftsmen and women at work, and even a gruesome buffalo sacrifice.

One of the special pleasures of the museum is the promenade around the grounds, where you can see a Khmer racing boat, a water-powered rice mill, traditional Cham houses, and the stilt houses of highland groups, many of them on stilts, and a gravehouse of the Giarai Cotu people. A special treat is the staging of traditional water puppet shows in an open setting.

Many museums in Vietnam are content to “stay in place,” but this one is still expanding, with occasional exhibitions and the addition of a building devoted to other Southeast Asian cultures.

CHAM MUSEUM IN ĐÀ NẪNG

In my (admittedly biased) opinion, the Cham Museum is far and away the best in all of Vietnam. The reason for this is twofold: 1) the Cham worked in brick and stone, and thus left a copious legacy that dates back to the 4th Century CE; 2) No one had shown much interest in the Cham ruins until French archeologists began excavating them in the early 1900s, and so they were able to accumulate a central collection in the Đà Nẵng museum. (Though some sculptures and artifacts did end up in Europe, as well as the National Museum of History in Hanoi.)

Balarama, older brother of Vishnu, holding a hand-plow;

Lord Ganesh; a giant Dvarapala (door guardian)

Cham sculpture tends to be overshadowed by that of the Khmer, especially the sculptural pieces from Angkor. But, the Cham were exceptional artisans. Ironically, the Vietnamese emperors were also great admirers of Cham art, bringing Cham sculptors and stonemasons back north from their periodic expeditions against the royal centers that they generically referred to as “Chiêm Thành” (Cham Citadel). One can still find traces of Cham workmanship in northern pagodas such as Chùa Thầy (west of Hanoi) and Chùa Thái Lạc (Hưng Yen province).

Upcoming: Museum of Trade Ceramics in Hội An (opened in 1994).

HISTORY MUSEUM – HỐ CHÍ MINH CITY

The History Museum in Saigon (Bảo Tàng Lịch Sử Thành Phổ Hồ Chí Minh) opened as the Blanchard de la Brosse Museum in 1929, the name being a nod to the governor of the colony of Cochinchina. Even though the museum has considerably less floor space than the two-story National History Museum in Hanoi, it has an important advantage in its collection of exquisite Óc Eo, pre-Angkorian Khmer, and Cham sculptures.

The Museum in Saigon has undergone two transitions: the first was when the French colonial administration turned it over to the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Vietnam. As Hue Tam Ho Tai has documented, the Museum’s focus during the “Republican” period (1955-1975) was on works of art, with designated galleries for Sino-Vietnamese art, art from the Óc Eo period, Cham art, Pre-Angkorean and Khmer Art, Japanese Art, and Thai Art.

The Museum’s galleries were extensively reorganized after the 1975 change in government, and it did not reopen until 1979. The primary theme was now the historical development of Vietnam, for the most following the Hanoi Museum’s chronological sequence of exhibits. The first room (prehistoric artifacts) is next to the main entrance, and the sequence proceeds clockwise through the legendary period of the Hưng kings to the centuries of “Chinese domination,” and the Lý and the Trần dynasties (Rooms 1-5). This is the history of the Đại Việt, a northern history—no attempt is made to connect the story with the parallel development of the Cham polities on the central coast and no mention is made of the conflicts that took place for many centuries between the Việt and Cham kingdoms.

This brings the visitor to the wings with the Museum’s stunning collection of statues from the southern region (Rooms 6 and 7). Here the exhibits are presented purely as art, stripped of any historical context. (Note that, although the signage for Room 6 only refers to Óc Eo, the hall has many fine pieces of Khmer art from the Mekong Delta.)

The historical sequence continues with a single hall devoted to Lê dynasty, the Mạc dynasty, and the “Restored” Lê dynasty. This is the traditional history created by the scholar-mandarins of the Vietnamese regimes in the north, based on the fiction that the Mạc emperors were no more than usurpers and that the Lê lineage was restored to throne and ruled in Thăng Long from the 1590s to the 1780s. What is omitted, as in the Hanoi Museum, is the history of the long struggle between the Trịnh lords—the de facto rulers in the north— and the rogue state of the Nguyễn lords on the central coast.

This omission is even more grievous in the Hồ Chí Minh City Museum, because, as Hue Tam Ho Tai has suggested, it has a special responsibility to tell the history of the southern region alongside that of the north. Limiting the presentation to the northern narrative leaves out the story of how the land of Champa and the Mekong Delta became part of the Vietnamese nation, a story that should include the commercial and cultural contributions of the Chinese immigrants who were pioneer settlers in Saigon and Biên Hòa.

Though the Museum’s attempt at history fails, it does have other rooms devoted to minority cultures of the south. One its unique collections is that of Vương Hồng Sển, who was curator of the Museum from 1948 until he retired in 1964. Sển was a noted scholar and writer, and, in many ways, the prototypical southerner. He was born in the Mekong delta province of Sóc Trăng, where it was not unusual to find families (like Sển’s)with Khmer, Chinese, and Kinh ancestry.

Upcoming: Museum of Hồ Chí Minh city (Bảo tàng Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh); Hồ Chí Minh City Museum of Fine Arts (Bảo tàng Mỹ thuật Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh); Nhà Rồng Wharf - Hồ Chí Minh Museum (Bến Nhà Rồng - Bảo Tàng Hồ Chí Minh).

- “Representing the Past in Vietnamese Museums,” Hue Tam Ho Tai, Curator (1998).

- Arts of Ancient Vietnam: From River Plain to Open Sea, Nancy Tingley, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, 2009. The exhibition catalogue from the extraordinary 2009-10 exhibits at the Houston Museum and the Asia Society, with many rare pieces from national and private collections. 368 pages, with color illustrations and expert commentary.

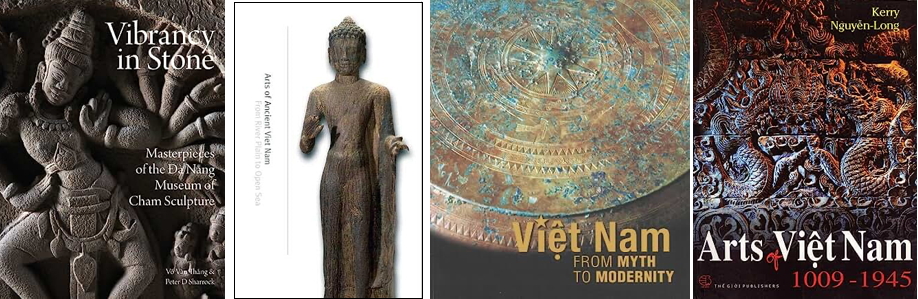

- Vibrancy in Stone: Masterpieces of the Danang Museum of Cham Sculpture, Peter D. Sharrock, Vo Van Thang (Editors), River Books, Thailand, 2018.

- Vietnam Museum of Ethnology: The Making of a National Museum for Communities, Nguyen Van Huy, 2010.

- Viet Nam: From Myth to Modernity, Heidi Tan, Asian Civilisations Museum, 2013.

- Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, John Guy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014.

- Arts of Vietnam: 1009-1945, Kerry Nguyen-Long, Thế Giới Publishers, Hanoi, 2013.

- Art ancien du Viêt Nam : Bronzes et céramiques, Pierre Baptiste, Ian Glover, 5 continents, 2008.

- Art of Vietnam, Catherine Noppe, Parkstone Press, 2003.

- Viet Nam: Collection vietnamienne du musee Cernuschi, Éditeur Association Paris-Musées, 2006.

- The Elephant and the Lotus: Vietnamese Ceramics in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Philippe Truong, MFA Press, 2008.

- Museums Of Southeast Asia, Iola Lenzi, Archipelago Press, Singapore, 2004