VĂN MIẾU: The Temple of Literature

I visited the Hanoi’s Temple of Literature in 1999, taking pleasure in its lovely setting but somewhat adrift when it came to the significance of its courtyards, ornamental pools, and low tile-roofed galleries. Being a writer, I have paid my respects there many times since, and learned to appreciate its development in stages.

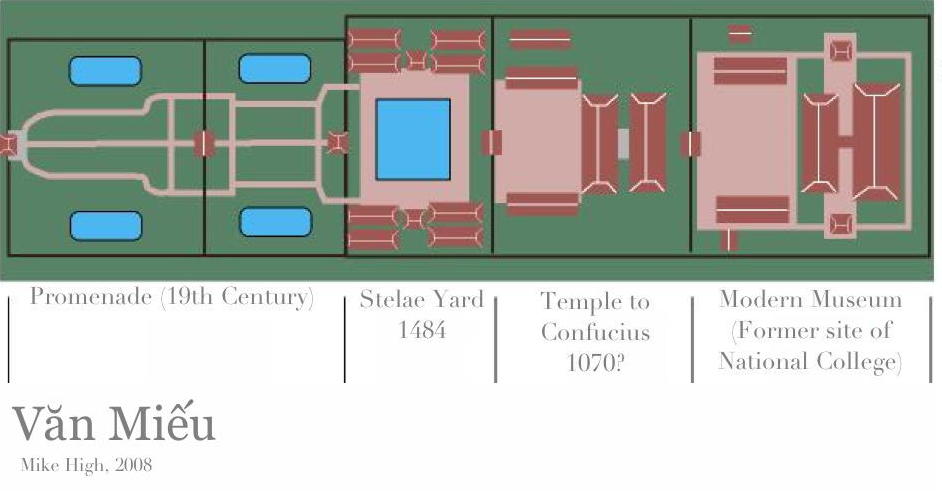

The Temple to Confucius. The royal chronicles state that the Văn Miếu was established in 1070, but this is not quite accurate. Trần Hàm Tấn (see notes) and others have argued that this term was applied retroactively by the historian Ngô Sĩ Liên, who presented his comprehensive history to the emperor in 1479. As modern scholars point out, the term Wenmiao 文廟 (Văn Miếu) was not adopted in China until the Ming Dynasty, and the Vietnamese court followed the Chinese lead in such matters, not the other way around. Tấn suggests that the work performed in 1070 was the restoration of a Confucian temple that had been established during the time when northern region of Vietnam was a province of Tang China.

The temple is a place for state officials to worship one of the foremost spirits in the imperial pantheon, but to understand its meaning, we have to start with a man of flesh and blood. Confucius (Khổng Tử, 551-479 BCE) was a reform-minded minister and philosopher who lived in the “Spring and Autumn Period” of the Zhou dynasty. When his political projects were thwarted, he established himself as a teacher with many scholarly disciples. He was a great believer in the importance of the classical rituals as the foundation of a harmonious state, but none of his contemporaries could have anticipated that he would later be honored by those very rituals.

According to Thomas Wilson, the first imperial sacrifice to Confucius was carried out in the Han period, but it did not become a regular ritual until much later. The Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) was the first to elevate Confucius to “royal status” in the pantheon of ritual deities. We may surmise that the first Vietnamese temple to Confucius was constructed in that period upon the orders of one of the prominent governors of Giao Chỉ (the name of the Chinese-governed province).

The first Vietnamese dynasties to rule in Hanoi (the Lý and Trần, 11th-14th centuries CE), favored a mix of Buddhist and local ritual practices, while retaining scholars at court who studied and followed the classical Chinese texts. Hồ Quý Ly began to incorporate Chinese bureaucratic and ritual conventions in late 14th century, but it was during the reign of Lê Thánh Tông (1460-1497) that institutions such as the Temple of Literature were fully developed.

Central altar to Confucius, with side altar to two of his four most famous disciples. Photo from 2014 visit.

Thus, the worshipping hall for Confucius was always the central structure in the Văn Miếu complex. Visiting today, we see several statues in this chamber that are said to represent Confucius and his primary disciples. They are said to date to the early 18th century, but that does not mean that they have always been here. There were periods in China when the use of statues in Confucian temples was considered improper—instead, he and his disciples were to be represented by tablets inscribed with their titles in Han characters. The second Nguyễn emperor, Minh Mạng, seemingly subscribed to this iconoclastic convention. Thus, even if these statues were originally created for the Văn Miếu, they may not always have been on display at the ceremonies conducted by high mandarins.

The Stelae Yard

The stelae-yard of the temple, with dates and hundreds of names of eminent scholars carved on stone tablets on the backs of sculpted turtles, is the richest in historical detail. The tradition of memorializing the graduates of the imperial examinations, begun in the early Ming period in China, was adopted in the year 1484 by Lê Thánh Tông, the fourth emperor of the Lê Dynasty.

Carving stelae was a labor-intensive project involving skilled artisans, and so we find that many were carved en masse when circumstances permitted, covering as many as two dozen earlier examinations. Revolts and succession crises sometimes created gaps in the triennial examinations, but from the time of Lê Thánh Tông, the Vietnamese emperors tried to maintain the tradition of erecting stele to the successful "laureates." The imperial examinations were relocated to the new capital in Huế in the early 1800s, and so you will find a similar stelae courtyard for the 19th-century scholars at the Temple of Literature on the Perfume River. (It is also worth noting that many of the older provinces in the Red River region maintained their own temples to Confucius, often with stelae recording the successful scholar from that province—such provincial and regional Văn Miếu are much rarer to the south.)

The irregular grouping of stelae is evident even from a distance, as in these views—an early colonial-era postcard, and my own photograph ca. 2005. The tiled roofs over the rows of turtle-stelae were a part of the modern restoration, which was justified by research indicating that the stelae were similarly sheltered in pre-colonial times.

The Mystery of the Missing Stelae. A careful comparison with imperial records indicates that there are many “missing” stelae—either not carved or removed. I became curious about this after noting that most of the missing stelae belonged to the Mạc Dynasty period. The Mạc were the ruling family in Hanoi from 1527-1592 and were proud followers of the Confucian tradition; however, only one stele remains from the examinations that they conducted while in Thăng Long. The Mạc were scrupulous about holding regular examinations as a sign of their enlightened administration. Nola Cooke counts 22 Mạc examinations during that time, and they even held an examination in remote Cao Bắng province shortly after being forced out of the royal capital. (That was the examination with the first and only female “laureate,” Nguyen Thị Duệ, who disguised herself as a man and became the imperial tutor after her deception was discovered.)

One explanation—attributed to the 18th century scholar Lê Quý Đôn—is that the financial burden was too great, given that the Mạc were occupied with suppressing the Lê restoration movement. This does not ring true, as the Mạc actually flourished for several decades in Hanoi and there were long periods of stalemate and coexistence in which the Lê coalition contented itself with control of the Thanh Hóa region. It is particularly telling that the Mạc are still credited with erecting a stele in 1536 for a Lê-period examination from the last years of that dynasty. It is inconceivable that they would have gone to such trouble without also erecting stelae for their own examinations of 1532 and 1535.

The better explanation is that the Lê loyalists destroyed most of the Mạc stelae after they entered Hanoi in 1592. The “restored” Lê regarded the Mạc dynasty as illegitimate, and thus would have been eager to erase the memorials to their accomplishments in the cultural sphere. This is borne out by the two Mạc-era stelae that remain. The 1536 stele commemorated a Lê examination, and the 1529 Mạc examination took place during the interregnum between the reign of the last emperor of the “Later Lê” (1522-1527) and the proclamation of the first emperor of the “Restored Lê” (in Thanh Hóa in 1533).

Since the stelae are not in chronological order, or even organized by reign, it is a bit difficult to compare the styles while walking around. This stele for the 1589 examination (which must have been conducted in Thanh Hóa) is decorated with two phoenix and the sun, a motif that alternated with two dragons and the sun. It was carved in 1653, in the first group of twenty-five stelae erected in the time of the Restored Lê. The royal script below begins with the standard phrase “stele for the foremost scholars (tiến sĩ) of the examination of year”—followed by the year and reign period of the examination.

After consulting several studies of the Văn Miếu, I have found it most convenient to group the stelae in the following manner:

| 1. | Eight stelae erected during the reign of Lê Thánh Tông. (The first seven stelae were erected in 1484; another was erected in 1486/7.) |

| 2. | Four stelae erected during the remainder of the Later Lê Dynasty (between 1496 and 1521). |

| 3. | Two stelae erected by the Mạc Dynasty (The first stele was erected in 1529 to commemorate the Mạc examination of that year; the second stele was erected in 1536 to commemorate the Lê examination of 1518.) |

| 4. | Twenty-five stelae were erected in 1653 in the time of Lord Trịnh Tráng, under auspices of the Lê Dynasty. (Includes six stelae to commemorate examinations held under the Lê emperors during their exile in Thanh-hoá province, examination years 1554 to 1589.) |

| 5. | Twenty-one stelae were erected in 1717 in the time of Lord Trịnh Cương (Commemorating examinations subsequent to 1653 held by the Lê Dynasty) |

| 6. | Twenty-two stelae erected during the remainder of the Restored Lê Dynasty. (Examination years 1718 to 1779). |

The Museum. An enormous two-story building has been constructed to fill out the fifth section of the complex, where the "national college" (Quốc Tử Giám) once stood. It is not historically authentic, bearing no resemblance to the original arrangement of dormitories and lecture halls, but it does have an interesting collection of artifacts, such as scholar's and mandarin's robes, doctor's degrees, and a portable bookcase that scholars would have carried along with them to the mandarin examinations. The statues in this hall are standard-issue modern bronze castings of the type that have been added to many historical temples.

Note on “Confucianism”: The phrase “Confucianism” as used in western texts is an approximation of the Chinese “rujiao” (儒教, nho giáo in Vietnamese). Ru means “letters” and jiao means “teachings,” where “teachings” has the connation of a belief system or school of thought. In the same sense, Buddhism is called Phật giáo and Taoism Đạo giáo, and these philosophies are often combined with nho giáo in the the tam giáo 三敎, “three teachings.” In Vietnam, such scholars are called nhà nho, frequently translated as “literati.”

- "Étude sur le Van-miêu de Hanoi (Temple de la Littérature)," Tran Ham Tan, Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient, 1951. Available on-line at the BEFEO site.

- Văn Miếu, the temple of literature, Ernst Sagemueller, COVIT-Consultancy Vietnam International Tourism, 2001

- Văn Miếu, Quốc Tử Giám (Le Temple de la Littérature), Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2004 • Thi Xử Nho Giáo, Royal Exams, Hữu Ngọc and Lady Borton, Thế Giới Publishers, 2004.

- Văn Miếu, Quốc Tử Giám, và 82 bia tién sĩ, Ngô Đức Thọ, NXB Hà Nội, 2002.

- The sacrifice to Confucius is described by Father Adriano de St. Thecla in Opusculum de Sectis apud Sinenses et Tonkinenses (A Small Treatise on the Sects among the Chinese and Tonkinese), translated by Olga Dror, 2002, pages 86-117.)

- ”Confucianism" in Vietnam: A State of the Field Essay,” Liam C. Kelley, Journal of Vietnamese Studies (2006) 1 (1-2).

- “Vietnam as a 'Domain of Manifest Civility' (Văn Hiến Chi Bang),” Liam Kelley, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Feb., 2003).

- “Social Organization and Confucian Thought in Vietnam,” John K. Whitmore, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Sep., 1984), pp. 296-306.

- “Sacrifice and the Imperial Cult of Confucius,” Thomas A. Wilson, History of Religions, Vol. 41, No. 3. (Feb., 2002), pp. 251-287. 1995)